We Need to Nuke the Japs Again

The plan was set, and at present there was no turning back. The countdown had begun for Capt. Robert A. Lewis, Sgt. Melvin H. Bierman and the 67 other Americans who would soon exist taking off on a mission to Hiroshima that only a few of them fully understood.

Years of top-secret planning, laboratory heroics and daredevil test flights over desert in unproven B-29 bomber planes had come up down to this in the early-morning hours of Aug. half-dozen, 1945: a six-hr, 1,500-mile flight from Tinian, a friendly island in the generally hostile Pacific, to Hiroshima, where we would drib "the big one" on Japan.

Soon, it would be no undercover what the United States had been up to since the bombing of Pearl Harbor. And so in the final hours earlier take-off, Ground forces contumely told the men to write their final messages home and give them to the chaplain — merely in case they didn't come up back.

Bierman, the Jewish son of a clothing retailer from Passaic, knew something was upward, although he couldn't —or wouldn't — say what. He was young: merely 5 years before, he'd graduated from Passaic High School, a member of the History and Drama clubs.

"This night, I am going on a mission that will get down in history," he wrote to his parents. "It's a dream mission, the mission that any American man would be proud to be of. It may be the greatest single cistron to brand the Japs surrender unconditionally."

'Nobody wins at war'

Bierman, 23, was a tail gunner aboard the Necessary Evil, one of 2 support planes that accompanied the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the bomb that morning time. In the cockpit of the Enola Gay and serving every bit co-pilot was Lewis, only 26, a Ridgefield Park native who only a few years before had led his high school football squad to the state championship.

As the mushroom cloud rose over Hiroshima, Lewis scribbled into his flight log the words that still haunt 75 years later:

"My God, what accept we done?"

Similar the other 67 Americans who participated in the Hiroshima mission, Lewis and Bierman are long gone. On the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and, three days later, Nagasaki, no ane who was aboard planes is live — although their story is preserved through oral histories maintained past the Atomic Heritage Foundation and the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History, and in the piles of letters, newspaper clips and heirlooms kept mainly by the children of the Atomic Historic period.

Bierman, who served every bit a tail-gunner aboard on both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki missions, was ane of the coiffure members charged with taking pictures afterwards the explosions. He produced some of the first images of the mushroom deject, pictures that Bierman's son, Mitchell, has hanging in his home in Randolph, with a handwritten note from his father.

"Picture I took equally we were getting out of the way when the 'mushroom' came up higher than was predictable," Bierman wrote. "We just got out of the way in time — otherwise we would have been roasted."

The war effectively concluded v days subsequently the bombing of Nagasaki, when Japan surrendered. Mel Bierman came abode to Passaic to the family business, selling wearing apparel — and became quite successful, opening Stage Iii shops in Passaic and Upper Montclair, and afterwards buying Ginsburg'southward, a high-terminate ladies' store downtown on Main Avenue.

Mitchell was born in 1962, 17 years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He was the youngest of three children built-in to Mel and Ballad Bierman — Anne being the oldest, followed by Louis. His parents were partners in the habiliment business, and the family lived a comfortable centre class life on Idaho Street in Passaic.

Story continues below the gallery.

"My father worked in the front of the store, doing all the schmoozing and hiring," Mitchell said. "My mother worked in the back, doing the books."

Mel, who died in 2013 at age 91, put together a ninety-folio memoir that Mitchell now has. The son too keeps his male parent's uniform and the Air Medal he received for the A-flop missions in a glass instance.

Like many veterans, Bierman didn't talk much about the war, but was proud of his role in it. One time the nuclear genie was out of the bottle, the globe never be the aforementioned, and the arms race was on. In their writings, Bierman and Lewis remained convinced that two atomic bombs that initially killed more than 200,000 people ultimately saved more lives by forcing Nippon to surrender.

Mitchell said his begetter regretted the tremendous loss of life, "but felt that in that fourth dimension, and in that place, it was the right thing to do. Not that he was basking in the glory of having been part of that. But he felt that if the enemy got the bomb, they were going to use it. Those casualties could have been our casualties. Nobody wins at state of war."

Return to Due north Jersey

While Bierman sold dresses, Lewis returned abode from the war to sell processed. He worked at the Henry Heide Candy Company in New York and for Estee Candy Company in Parsippany, making sweet confections in between attending the occasional reunion with the Hiroshima crew.

North Jersey:One-time WWII veteran, author Robert Leckie honored with imprint in downtown Rutherford

Column:From opposite worlds, ii soldiers forged a friendship — and saved each other'south lives

Lewis never publicly regretted the bombing, simply information technology appears that he did go tired of having to defend it. He expressed his frustration in a 1975 interview with The Record, thirty years after Hiroshima.

"The bombing of Hiroshima is something that is over with. What good is it going to do us to talk virtually it?" he said. Lewis added that the ensuing nuclear artillery race had effectively led to a stalemate.

"Today I'1000 pleased the bomb hasn't been used again. I promise it has become a deterrent force, and maybe we won't accept so many wars," he said.

In the years later on Hiroshima, Lewis had a falling out with Col. Paul W. Tibbets, whom the Army selected over him to pilot the aeroplane that dropped the flop. Lewis was considered 1 of the all-time and near daring pilots in the Air Forces, a man who twice had crash-landed only saved his crew both times.

Lewis had once flown with Charles Lindbergh on a newly minted B-29 Superfortress and received the famed aviator's approval. Lewis had flown hundreds of missions but had no combat experience, and the Ground forces put Tibbets in command of the Hiroshima mission.

To add insult to injury, Tibbets took command of the B-29 that Lewis was flying, and even replaced some members of the crew. And then Tibbets named the plane the Enola Gay, after his mother.

Flim-flam News host Chris Wallace reports in his new book, "Countdown 1945," that Lewis became "livid" when he saw "Enola Gay" painted on the nose cone a day before the mission.

"This was it, the final indignity, Lewis raged," Wallace writes. "Commencement Tibbets bumps some of Lewis'south regulars from the crew. Then Tibbets decides he'due south going to pb the mission. Now this?"

'A mission that volition go down in history'

The Enola Gay took off at two:45 a.m. on Aug. 6, with Lewis assuming the role of co-airplane pilot. A New York Times reporter, William Laurence, asked Lewis to keep a log. A copy of that handwritten log is kept at the Aviation Hall of Fame & Museum of New Bailiwick of jersey at Teterboro Aerodrome.

Lewis describes the moment the bomb dropped, when the plane made a sharp turn and the crew braced for the flash and explosion. Two members of the crew forgot to put on their dark welder's glasses, Lewis wrote.

"Then in about 15 seconds after the flash, there were two distinct slaps on the ship and that was all the physical furnishings we felt. I turned the ship so we could observe results and there in front our eyes was without a dubiety the greatest explosion man has always witnessed."

Equally the Enola Gay high-tailed back to Tinian, Lewis struggled for words to describe what he felt.

"I am certain the unabridged coiffure felt this experience was more anyone man had always thought possible," he wrote. "It just seems incommunicable to comprehend. Simply how many did we kill? I honestly accept take the feeling of groping for words to explain this. I might say my God what accept we done."

Leaving their mark

Lewis returned home after the war and at various times lived in Ridgefield Park, Maywood and Lake Mohawk in Sussex Canton, according to newspaper clippings. He likewise dabbled in sculpture, and afterwards in life became an abet for a nuclear artillery freeze, according to his obituary. He was living in Virginia when he died in 1983 at age 65.

The business firm in which he grew up, at 28 Hazelton St. in Ridgefield Park, even so stands. Ironically, today a history instructor lives correct next door.

"Yes, I know who used to live there," Paul Bouchard said when he answered the door one day recently. Bouchard, 51, teaches at Ridgefield Park Loftier Schoolhouse and says he tells the Lewis story, only feels that the atomic flop doesn't have as much resonance with teenagers as when he was a kid.

"I think for this generation, 9/11 is the defining event," he said. "And near of the kids going to high schoolhouse today weren't even born when 9/11 happened."

Bouchard said he grew up in Oradell and had several neighbors who served in World War II. "The Cold State of war was a very real thing to me," he said. "Do I think Hiroshima and Nagasaki have relevance today? Admittedly."

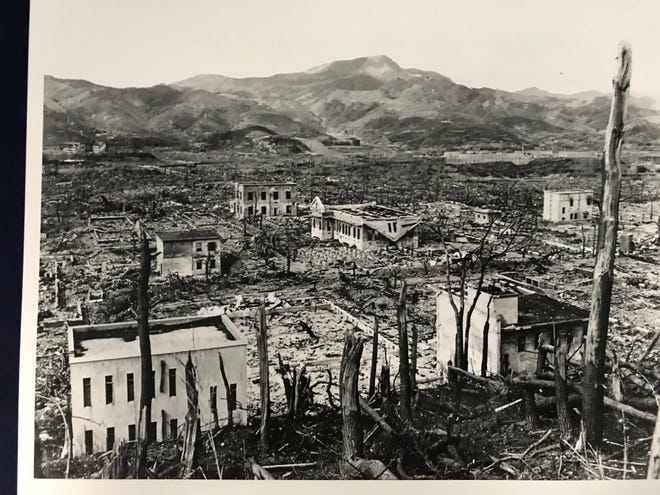

The destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was the culmination of the Manhattan Project, the race to split the atom and build the ultimate weapon. Although the Manhattan Projection was peak-secret, building the bomb ultimately required more 600,000 people involved in all sorts of tasks.

One of them was Bierman, who dropped out of NYU to join the Army when the state of war broke out. He was initially assigned to an Infantry unit at Fort Jackson in South Carolina, until he was mysteriously plucked from his unit of measurement and put on a train bound for Miami.

"To his dying day, he didn't know why he was selected," his son Mitchell recalls. "The Army never told him, and he didn't ask. There's a give-and-take in Yiddish, 'beshert,' which means 'destiny.' My male parent believed that it was meant to be."

In a memoir that Mitchell has compiled based on tapes his father recorded earlier his death in 2013, Bierman tells how he was lying in a foxhole during training in South Carolina when a sergeant approached in the middle of the night and said, "Follow me."

"I didn't say goodbye to my buddies or my group at all," Bierman wrote. "I simply left. I was torn away." He was put on a train to Miami, the start of an odyssey that would take him to tail gunner's school and ultimately to Wendover Field in Utah, where the Army was assembling the B-29 crews for the atomic bomb drops.

Like many veterans, Bierman didn't boast about his service, although he was proud of his contribution. And he risked his life, like the others, and felt no need to repent.

His girl, Anne Bierman Cion Grunberger, recalls bringing her begetter into her history form in junior loftier school during the 1960s to tell the story.

"At that place was non a moment that he regretted it," she said. "Considering he felt if we didn't become them, they were going to go usa. He always said it was the right thing practise. We always said, 'Dad, why did they cull y'all?' And he always said, 'I have no thought.' "

In addition to his work in the clothing business, Bierman became deputy mayor and president of the Bedchamber of Commerce. In a 1980 interview with the Herald News, he acknowledged that Hiroshima and Nagasaki should never happen again.

"It is a good argument against whatsoever more war, and they should prove pictures of what happened [at Hiroshima and Nagasaki] often," he said.

Richard Cowen covers Superior Court in Passaic Canton for NorthJersey.com. For unlimited access to the most important news from criminal trials to local lawsuits and insightful assay, please subscribe or actuate your digital account today.

Email: cowenr@northjersey.com

Twitter: @richardcowen123

Source: https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/2020/08/06/hiroshima-bombing-75-years-after-two-nj-men-who-flew-mission/5572216002/

0 Response to "We Need to Nuke the Japs Again"

Post a Comment